Supes and Bats in Bowling Shirts: Dexter’s Dark Avenger

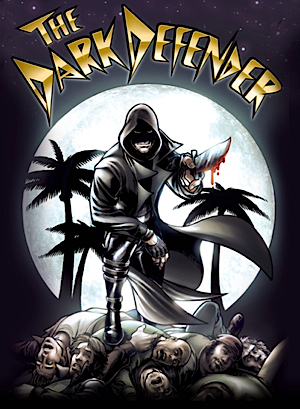

the Dark Defender

Dexter, Season 2

Dexter’s season one self-image begins with the smug self-loathing of a monster, aware that only his conditioning allows him any place in society outside a jail cell. Confronted with two like-minded sociopaths he was unable to force into his mold, he began to see himself as a different and better breed of monster, one who may someday be able to genuinely connect with others as he is. He sees the crowd of curious onlookers as cheering fans, with Deb at his side, smiling and sharing in his applause:

Everyone else would probably thank me if they knew I was the one who drained [the ice truck killer] of his life. Deep down, I’m pretty sure they’d appreciate a lot of my work. This is what it must feel like to walk in full sunlight, my shadow self embraced.

While this is a mixed sign in terms of real progress – retreating into fantasy rather than approaching the issues that the second season will stagger through – the immediate effect is to question the modern heroic archetype: the vigilante superhero.

The show does suffer the requisite sophomore slump, abandoning some of the best first-season elements while deepening the concept’s reach and mythology. While the first season mined and transcended a pulpy beach novel, the second too often lived down to the potboiler source material. One plot thread is painfully predictable: OMG Crazy Hot Girl Is The Only One Who Understands Me And Thus We Must Fuck, which segues into OMG Crazy Hot Chick Is Crazy And Hot, In The Sense That She’s Really Into Emotionally Strategic Arson!

Urgh. Even Dexter’s long delayed leap into sexual puberty can’t justify the stretching of this from its one-episode premise through three-quarters of the short season.

A larger issue was the too-convenient resolution of Dexter’s various cliffhangers. Too often, he is a cipher serving only to bring together the awkward thesis and antithesis that independently resolve his crisis. The long-awaited confrontation with Rita about the real reason her abusive ex-husband was found with a heroin needle sticking from his arm (leading to his re-incarceration and fatal shanking) is derailed after Dexter has been forced to confess – when Rita conveniently jumps to the conclusion he must be an addict himself, apparently forgiving him. This leads Dexter to Narcotics Anon, where he is presented with the season arcs of aforementioned batshit insane hot chick and the addiction filter through which to explore his compulsions. The investigation into the Bay Harbor Butcher (ie Dexter) and the personal persecution of Sgt Doakes crash together, leaving Doakes the top suspect with Dexter’s blood sample trophies in his trunk. Doakes again, stashed in a remote cabin that’s about to be found by the FBI’s great white hunter – not to mention made a connection with Dex and nearly convinced him to turn himself in – is found and spontaneously killed by Batshit Crazy Hot Chick. Who then ties off her own loose end by very publicly demonstrating her insanity and fleeing the country, to be killed by Dexter at his leisure.

Dexter’s contribution to his crises and moral quandaries is little more than ethically facile mopping up. Following the insane woman’s version of the NA programme, he spends months attempting to quit his addiction – allowing Rita, Doakes, and Batshit Crazy Woman to believe he is struggling with heroin – and delve into his shadowed past, particularly the grimier aspects of his formerly sainted foster father. He reaches a breaking point when Doakes witnesses him murdering, and Doakes’ sickened reaction forces him to put together two memories he’d previously managed to keep separate: his father’s horror at witnessing Dexter happily dismember a victim picked according to “Harry’s code” and his father’s suicide soon after.

Dexter’s guilt and misery evaporate soon after when he realises God must approve of his actions, having rescued him from capture via a complicated spiderweb of contrivances; sadly, Dexter lacks to self-awareness to consider the possibility of showrunners sparing his viewers from having to make a real judgement on his actions and their own complicity in his actions, their attention literally continuing his existence.

The hints at superhero traits offered in the first season are laid out without subtlety. One local graphic artist has literally made a comic hero of the Bay Harbor Butcher: the Dark Avenger. (Dexter is fascinated by the image but only notes that dark leather would be completely impractical for Miami.) He enters the season thinking that ordinary people would cheer him on and indeed they do, as an abstract concept. When a face – Sgt Doakes’ – is put to the killer, the acclaim disappears.

As Dexter-the-killer, he exposes the childish morality of superheroes who get the bad guys without killing them. Batman and Superman are condoned by the police in their world, delivering criminals to Headquarter’s front door – although you have to wonder how their cases ever went to trial. Much like Dexter, their verdict of ‘guilty’ is the only law. The criminals who have to die for plotty goodness or the satisfaction of a network’s moral code generally cause their own doom, usually by refusing to grab the hand of the person who’s been whaling the life – nearly – out of them for the past several minutes and plunging to their comic-book death.

The show itself resolves the irresolvable in a similar slight of hand, having Lila (a self-deluding murderer-by-arson who seeks out vulnerable new victims) do the dirty work of killing Doakes (a self-confessed monster who admits to isolating himself for others’ safety). Dexter’s ‘code’ remains intact through others’ actions; while Doakes got a raw deal at the end, his obsessive bullying directly led there.

Dexter’s backstory riffs on two of the oldest comic book heroes, recognisable in any part of the world with any access to visual media. He is a superman hiding in plain sight – like Clark Kent, he is physically and intellectually stronger than most; like Bruce Wayne, he builds his ‘true’ persona with technological preparation and stringent training. His motivations…they are something of a different story, but not from a distant shelf. The motivations of the hero and the serial murderer may only be chapters of the same book.

The foundling is raised by a foster father who knows his beloved son is not like other children, who instils a rigid code and the need to hide his difference above all else. Ostensibly on the side of the angels – he wants his strange son to have something of a normal life, unmolested by authority, while using his abilities to make the world a better, safer place – the impotent father conditions him into a black-and-white worldview to further his own agenda. Isolated from other influences – to keep the dangerous secret of his difference secret, of course – the son sees his father as the ultimate, unquestioned authority and is kept from developing an independent personality and the ability to truly take responsibility for his own actions. When the father has died and the son begins a long-delayed maturation process, he’s initially faced with an either/or: continue following the father’s law to the letter, or reject all morality in favour of showy self destruction.

Or: the boy is orphaned by a gruesome murder that will haunt his psyche through adulthood. As a nemesis could later observe, he had a bad day, and everything changed – he became a vicious freak, avenging that long-ago trauma on present individuals who are innocent of that crime, if not others. Only a personally enforced code keeps him morally separate from those he hunts.

Unlike Clark or Bruce, Dexter actively reminds himself that he is a monster – usually forcing himself into an emotionless archetype he doesn’t actually fit – despite his code. Those other American heroes cling to their codes as the thing that makes them the opposite of the criminals they use violence and intimidation to apprehend. Dexter knows he would still kill without the veneer of justice. The abilities and the need to use them precede any thirst for justice.

Would Bats and Supes do the same in a more realistic world? Where society – or at least its legal system – demanded that only the police force, with its flawed systems of oversight and restraint, use physical force to “protect” society and remove its worst elements?