Kick-Ass: why?

“What works on the page doesn’t always work on the screen, asshole.” – Dave Lizewski

Of the two Kick-Ass texts, the comic is far more faithful to the world it depicts (one seemingly defined by a lack of Alan Moore). The fundamental difference is that the graphic novel blatantly loathes its audience – and is therefore able to more accurately and comically present that group’s foibles and masochistic fantasies – while the film abandons this worldview mid-Act 2 in favor of pandering to the demographic.

Dave Lizewski is an Asperger’s-esque teen who suffers from what he describes as “the perfect combination of loneliness and despair,” which drives him to nick an identity from the comics he adores (obsessively, of course – no fictional fan has any other interests). The film and comic diverge pretty quickly, despite a surface similarity. Both present the sudden but natural death of Dave’s mother as both a vague motivation and something to be resented for lacking a good revenge arc. Neither seems to mourn very much, only noting the effect it’s had on Dave’s dad, who would do well to attend a support group hosted by Charlie Swan. Movie-Dave is a lovable loser who tries to make friends with those even more socially outcast than his geek-clique and picks two men who’ve repeatedly mugged him as his first heroic effort. Comic-Dave seethes with resentment that others don’t see how wonderful he is and picks relatively harmless-looking graffiti taggers as his first target. Unexpectedly (for the genre), both Daves fail spectacularly and spend several months recovering in hospital, and both choose to continue putting their bereaved father through financially ruinous hell rather than give up their delusional identity.

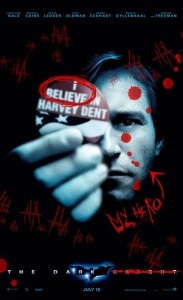

Watchmen was one of the first in-universe texts to confront the fact that anyone who chose the vigilante lifestyle would not only be mentally disturbed but probably only make the world a more dangerous place through their efforts. Kick-Ass attempts to update this concept to the 21st century by using cell phone cameras and Myspace as a direct conduit to Coincidental Broadcasts, upping the childish cynicism by half, and lowering expectations of audience IQ by at least as much. One cover announces its mission statement for the slower readers:

And yet the comic is less insulting than the film, which promises graphic deconstruction and provides Rambo-esque clichés. Dave gets beaten down, but then gets Real Mad and kills bad guys with a Gatling-enhanced jet pack and a rocket launcher (with no fear of the justice system). He gets the assigned most beautiful girl in school, after shamming as a GBF in order to amass the Nice Guy points that will make her owe him a relationship. He rescues one of the city’s only genuine superheroes and becomes he school “protector.”

All this with nary a synapse spark over committing mass murderer.

In a straight popcorn flick, this might be good enough, given that Kick-Ass was the hero of the movie named after him. But he’s not. He’s a mildly irritating prologue glommed onto Big Daddy and Hit-Girl’s star turn. From the moment the appear on screen or paper, , Kick-Ass becomes part of the audience. This works – on its own level – because the father-daughter team is both more competent and far more interesting than the talentless and asocial imitative fanboy. Watching real superheroes do their thing is his natural level. The film demands a suspension of disbelief and basic humanity appropriate to a later Die Hard sequel, then flings an affectless and brainwashed 11-year-old serial killer at us.

She hacks and slashes her way through a room full of stereotypical thugs – and there is something primal and wonderful about that sight familiar to any fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, just as it’s oddly heartwarming that a father would train his daughter to be tough rather than decorative, how not to freeze when faced with the physical threats a small and pretty girl is likely to encounter as she ventures into the world.

But Buffy spent entire seasons mourning her lost potential of becoming someone who didn’t spend her nights killing other sentient beings. Hit-Girl and, more importantly, her father have no such qualms.

The film takes the easy route again by giving Big Daddy the standard Antihero’s Journey – a good cop framed by the Mob he refused to work for, which somehow leads to his wife’s suicide – and a clear mission of revenge. Comicverse Bid Daddy made this story up and picked a target at random. He was just an accountant, and obsessive comic book fan – an adult Dave Lizewski and obvious sociopath – who ran away from his career and wife into fantasy, kidnapping his daughter and raising her to live out his violent daydreams. He never comes near the bad guys, sending his daughter in alone and watching from a safe distance through the scope of a sniper rifle.

Hit-Girl, the only real superhero (and innocent), is the only comic character who catches a break in the end. She avenges her father’s completely deserved death and gives up mass murder in favour of a relatively normal (if bully-proof) life with her mother. Actually, Dave’s father, whom the comic never marginalises as much as the film does, also breaks even. His son gives up getting beat up and running up hospital bills, and he even begins to move on from his paralysing grief to begin dating again. Big Daddy and the local Mob branch all die badly, and Dave (thank god) is roundly rejected by the object of his obsession when he confesses his deception and “love.” He tries to comfort himself that he’s changed the world by inspiring a legion of mentally unbalances poseurs, but the last frame goes to one of these deluded souls, the Armenian about to become pavement pizza when his homemade wings fail twenty floors up.

The uncompromising comic is a far superior story…but neither is worth the time it takes to see – or review – them.